In recent years, more Polish marriages have been ending in divorce. Once known for low divorce rates thanks to its strong Catholic tradition, Poland is now seeing a steady climb in the number of marital separations. The divorce rate in Poland – the number of divorces per 1,000 people – has risen from historic lows. This trend raises questions: Are marriages under new pressures, or have social attitudes changed? In this article, we’ll dive into the data and expert insights to explain the upward shift. We’ll look at historical trends, reasons behind rising divorces, regional patterns, effects on families, societal responses, and how Poland compares with other European countries. By the end, you’ll understand the key factors driving Poland’s climbing divorce rate.

Historical Trends in Poland’s Divorce Rate

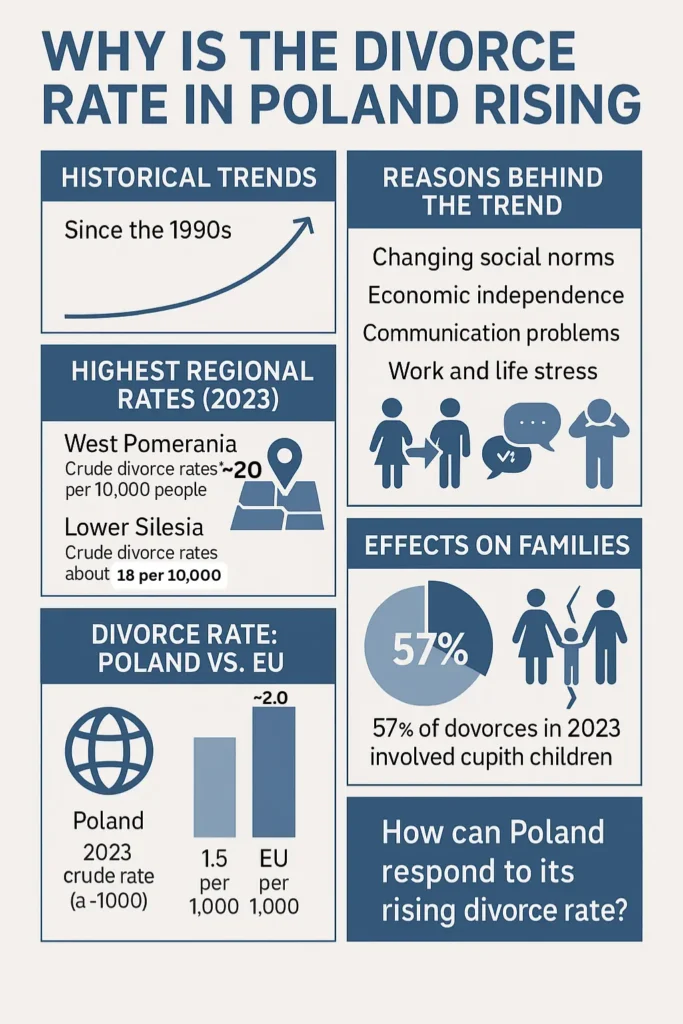

Over the past few decades, Poland’s divorce rate has gradually climbed. In the 1990s, shortly after the fall of communism, roughly 40,000 divorces were recorded annually. Since then the number grew, reaching a historic peak around 2010. For example, one report notes that about 61,300 divorces were granted in 2010. Meanwhile, the number of new marriages fell sharply (from over 228,000 in 2010 to about 145,900 in 2023), meaning a larger share of those unions ended in divorce. Although final divorce counts dipped during the COVID-19 pandemic (only ~51.2k in 2020 due to court closures), they rebounded quickly afterward. By 2023 around 56,900 divorce petitions were filed, about 3% more than in 2022. Despite short-term dips, the long-term trend is clear: Poland’s divorce rate has almost doubled since the 1960s. According to Eurostat, the EU crude divorce rate rose from 0.8 per 1,000 in 1964 to about 2.0 per 1,000 in 2023 – and Poland has followed suit (albeit still below that EU average).

Key historical points:

- 1990s: ~40,000 divorces per year nationwide.

- 2010: Peak at ~61,300 divorces.

- 2020: Sharp pandemic dip to ~51,200 divorces.

- 2023: ~56,800 divorces (roughly 28% of new marriages).

Each year’s statistics show that, even as fewer couples are tying the knot, a larger fraction are choosing to split up. In fact, official data indicate that in 2023 about 28% of all marriages ended in divorce. This represents a significant rise from previous decades when divorce was relatively rare.

Reasons Behind the Trend

Several social and economic factors help explain why more Polish marriages are breaking down. Experts point to changing attitudes and new pressures on couples. Today’s spouses often have different expectations than past generations: there is less stigma around ending an unhappy marriage, and individuals place a higher value on personal fulfillment. As one family-law attorney notes, divorce in Poland is “no longer a taboo” and many modern women are financially independent, reducing the economic barriers to leaving an unsatisfying marriage. With both partners often working and sharing less traditional roles, the idea of staying “in an unhappy marriage at all costs” is fading.

Common factors cited by couples include communication problems, growing apart, and unmet expectations. For example, interviews with divorce lawyers reveal that clients frequently blame “lack of communication” and the pressures of modern life for their split. In the past, partners might have cited vague “character differences”, but today both spouses are more willing to seek solutions or end the marriage if those issues become intolerable. The rapid pace of life and work-related stress can exacerbate these problems. During the pandemic, for instance, being stuck at home together amplified conflicts; exhaustion from isolation and caring for kids while juggling work often made relationships fray more quickly.

Other key contributors include:

- Economic Independence: With more women in the workforce and earning their own income, many feel they can afford to separate. This financial freedom removes a traditional reason (economic dependence) for staying married.

- Changing Social Norms: Younger generations are more accepting of divorce as a solution to unfixable marital issues. There’s growing awareness of mental health and the idea that staying in a toxic relationship can be worse than separating.

- Lower Marriage Rates: Poland’s population of young adults has shrunk (there are far fewer 20-somethings than 40-somethings), so the pool of potential newlyweds is smaller. Even as fewer couples marry, the number filing for divorce has stayed relatively stable, which makes the divorce rate appear higher.

- Social Support Resources: More couples today are aware of legal options like divorce mediation and counseling. Poland has seen rising interest in mediation as an alternative path out of a failing marriage. This means some couples split more amicably and with professional help rather than staying in dysfunctional relationships.

In short, Poland’s rising divorce rate reflects a society in transition. Economic and educational advances, combined with evolving values about marriage, have changed how couples respond when problems arise.

Regional Divorce Trends

The increase in divorces is not uniform across Poland – it varies widely by region and city. Divorce statistics show a clear urban-rural divide. About 72% of divorces occur in urban areas, while only 28% take place in the countryside. On a per-marriage basis, big cities have much higher split rates: roughly 460 divorces per 1,000 new marriages in cities versus only 260 per 1,000 in rural areas. This suggests that city life – with its faster pace, different cultural norms, and perhaps more social acceptance of divorce – tends to produce more separations than traditional village life.

Among the cities themselves, the largest courts handle the most divorce cases. For example, Warsaw (which actually has two separate district courts) saw about 7,700 divorce petitions in 2023. The Poznań court handled around 5,400 petitions, the highest of any single court in Poland. Other major centers like Gdańsk and Kraków each handled about 4,000 petitions that year. In contrast, smaller cities filed only a few hundred cases; for instance, Przemyśl had only about 450 divorce applications in the same period. This again reflects population differences – big cities simply have more married couples – but may also hint at cultural factors like varying divorce norms or access to legal services.

At the regional level, some provinces stand out. In 2023, the Województwo Zachodniopomorskie (West Pomeranian Voivodeship) had by far the highest divorce rate, with about 20 divorces per 10,000 inhabitants. The neighboring Dolnośląskie (Lower Silesia) was also high at roughly 18 per 10,000. By contrast, the lowest divorce rates were in Małopolskie and Podkarpackie, at about 12 and 11.6 per 10,000 respectively. On an individual level, this means that regions like West Pomerania and Lower Silesia experience divorces at roughly twice the frequency of Podkarpacie. These regional patterns may reflect cultural differences (for example, Podkarpacie is known to be more religious/traditional) as well as economic factors.

Key regional points:

- Urban vs. Rural: ~72% of divorces in cities; divorce rate per marriage is ~460‰ in cities vs 260‰ in villages.

- Major cities (2023): Warsaw ~7.7k filings; Poznań ~5.4k; Gdańsk ~4.5k; Kraków ~4.0k.

- Highest regional rates: West Pomerania (~20/10k people), Lower Silesia (~18/10k).

- Lowest rates: Małopolskie (~12/10k), Podkarpackie (~11.6/10k).

These differences highlight how local culture and demographics influence the divorce trend. Nationwide, however, the overall rise applies to all parts of Poland, even if at different levels.

Effects on Families

A rising divorce rate means more Polish children and families experience separation. In 2023, roughly 57% of divorcing couples had at least one child, most often just one. This suggests that many divorces involve families with kids. In practical terms, tens of thousands of Polish children saw their parents split that year. Such separations can have significant emotional and financial impacts. Children often face the challenge of adjusting to two households, and parents must navigate new co-parenting arrangements. Social researchers warn that family break-up can lead to stress, anxiety, or academic problems for some kids – although the outcomes vary widely by situation.

For parents, divorce can also be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it may relieve a toxic or unhappy marriage, potentially improving life satisfaction in the long run. On the other hand, splitting one household into two usually strains household finances, especially if only one parent can work or pay alimony. Many families find themselves needing to adjust budgets, seek child support, or rely more on social programs after divorce. In summary, the social ripple effects of rising divorces touch education, healthcare, and welfare systems, as well as the lives of the individuals involved.

Despite the challenges, many Polish couples try to handle splits responsibly. According to lawyers, about 83% of divorces in Poland are processed as “no-fault” cases – meaning the court does not assign blame to either spouse. Only roughly 13% of cases in 2023 ended with one spouse found legally at fault (11% husband at fault, 2% wife at fault). This high rate of mutual or uncontested divorces suggests that many couples agree to part ways cooperatively, which can reduce conflict for any children involved.

Impacts on families include:

- Children: Many kids now grow up in single-parent or blended families, as over half of divorces involve couples with children.

- Emotional stress: Parents and children alike may experience grief, anxiety or uncertainty during and after divorce. Counseling and support services are often needed.

- Financial changes: Dividing assets and raising separate households can lower living standards. Alimony and child-support arrangements become important.

- New family structures: An increase in single-parent families, stepfamilies, and cohabiting couples alters the traditional family landscape.

Overall, a higher divorce rate reshapes Polish family life: it means more broken homes but also reflects growing recognition that staying together at all costs is not always best for everyone involved.

Societal and Cultural Responses

Poland’s society is adjusting to its climbing divorce figures in various ways. The Catholic Church, historically influential in Polish life, has expressed concern about the trend. Church leaders often lament that more couples are breaking the sacrament of marriage, emphasizing traditional family values. For example, Cardinal Kazimierz Nycz remarked that the scale of divorces had surpassed expectations (despite clergy efforts). However, public discourse is becoming more open. Media outlets frequently cover divorce statistics and stories, reflecting a gradually reduced stigma. Young Polish adults are also reportedly more aware of their legal rights in family matters. One expert notes that especially in bigger cities, people are “increasingly conscious of their rights” and less willing to stay in a “toxic” marriage.

Legally, divorce remains a matter for the civil courts. Poland does not have a system of quick divorces or liberal no-fault policies like some countries. Instead, courts require proof of irretrievable marriage breakdown, and spouses must agree on issues like property division and child custody to get a mutual-consent divorce. This fact means the rising number of divorces takes time to work through the system; even when couples agree, the legal process can take many months. As a result, the official divorce rate may lag behind the number of couples seeking separation.

On the flip side, the growing demand for family law services has spurred an expansion of counseling and mediation. Many couples now explore marriage counseling or divorce mediation rather than fighting in court. In fact, reports note that interest in mediation is growing year by year. These professional services are part of the societal response: Poland is building more institutional support for families in crisis.

In everyday culture, divorce is increasingly portrayed as a normal – if unfortunate – life event. Television programs, online forums, and social groups discuss how to cope with divorce, share advice, and normalize the idea that one can rebuild a life after a split. While there is still a cultural preference for lasting marriage, most Poles today no longer view divorce solely as a shameful failure. This shift in attitude is itself both a cause and an effect of the rising divorce rate.

Divorce Rate in Poland vs. the EU

How does Poland’s situation stack up against the rest of Europe? It turns out Poland’s divorce rate is below the EU average, even as it rises. In the European Union as a whole, about 0.7 million divorces occurred in 2023, translating to a crude divorce rate of roughly 2.0 per 1,000 people. Over the past decades the EU rate has roughly doubled (from 0.8‰ in 1964 to 2.0‰ in 2023). Within the EU, countries vary widely: Latvia (2.8‰) and Lithuania (2.5‰) had the highest divorce rates in 2023, and Finland about 2.1‰. Western European nations like France or Belgium also hover above 2‰.

By comparison, Poland’s divorce rate is lower. In 2023, the estimated rate was about 1.5–1.6 per 1,000 population (some sources list 1.6‰). In other words, Poland’s rate is roughly half of the highest EU figures, and significantly below the EU average. This means that, although divorces are rising, Poland still has fewer divorces per capita than many of its neighbors. For example, Germany’s recent rate is around 1.5‰ (similar to Poland) but countries like Denmark or the Netherlands are over 2‰.

This EU comparison highlights that Poland’s trend is part of a broader regional pattern of increasing marital separation. However, Poland’s traditionally conservative culture has kept its rate somewhat lower than those of Western Europe. As social changes continue, some analysts expect Poland’s rate might edge closer to the EU norm in the coming years – but any big shifts will likely lag behind countries where divorce has been common for longer.

Summary of EU context:

- EU average (2023): ~2.0 divorces per 1,000 inhabitants.

- Highest EU rates: Latvia (2.8‰), Lithuania (2.5‰).

- Poland (2023): ~1.5–1.6‰ – significantly lower than the EU norm.

- Trend: EU rate roughly doubled since 1964; Poland is following an upward path in the same era.

Conclusion

Poland’s rising divorce rate reflects deep social change. We’ve seen that after decades of stability, recent years have brought a clear uptick in marital breakups. This change is multi-faceted:

- Key data: About 57,000–81,000 divorce petitions are now filed yearly in Poland (2023 figures), with around 28% of new marriages ending in divorce. This gives a crude rate near 1.5–1.6 per 1,000. These numbers are higher than Poland’s past levels but still below the EU average (~2.0‰).

- Main causes: Shifts in society – notably greater gender equality, changing attitudes, and new stresses like modern work-life pressures – have made divorce more common. Many couples now cite communication breakdowns, unmet expectations and stress as reasons. Importantly, mutual consent divorces dominate (about 83% no-fault), showing that many splits are agreed to rather than adversarial.

- Family impacts: More Polish children experience parental separation than before: in 2023 over half of divorces involved kids. This poses challenges (emotional, financial) but also reflects a society where marital quality is taken seriously. Support systems like mediation are growing to help families transition.

- Regional picture: Urban areas and certain regions have much higher divorce levels. Big cities (Warsaw, Poznań, etc.) see most cases, and provinces like West Pomerania have the nation’s highest per-capita rates. In contrast, rural and more traditional areas still divorce much less often.

- European context: Poland’s divorce rate is rising in line with European trends, though it remains lower than in Western EU countries. According to Eurostat, the EU average crude divorce rate is about 2.0‰; Poland’s is closer to 1.6‰. The gap suggests that cultural factors and legal processes (which make divorce more complicated than in some countries) keep Poland’s rate relatively modest for now.

Overall, Poland’s increasing divorce rate tells us that many couples feel more able to end a marriage that no longer works. This has broad implications: policy-makers may need to bolster family support and counseling services, while communities adapt to new family structures. The key takeaway is that divorce in Poland is becoming more common, not because families care less, but because societal and economic changes give people more choices and higher expectations for partnership. As these trends continue, we should expect Poland’s divorce rate to remain under scrutiny both at home and in its comparisons with Europe.

FAQs

What is the current divorce rate in Poland?

Currently, Poland’s crude divorce rate is around 1.5–1.6 divorces per 1,000 inhabitants. In 2023 roughly 56,000–57,000 divorces were granted, compared to about 146,000 new marriages. That means about 28% of new marriages ended in divorce that year. In plain terms, for every 1,000 people in Poland there were about 1.5 divorces in 2023.

Has the divorce rate in Poland been increasing?

Yes. After years of steady growth from the 1990s through the 2010s, the number of divorces dipped briefly during the COVID-19 lockdowns but has since rebounded. For example, around 61,300 divorces were finalized in 2010, dropping to about 51,200 in 2020 during the pandemic, then rising again to roughly 56,800 in 2023. Overall the trend is upward, reflecting that divorces are now a more common outcome of marriage than before.

What factors are contributing to the rising divorce rate in Poland?

Experts cite several reasons: changing social norms (divorce is less stigmatized), greater financial independence (especially among women), and modern life stresses. Many couples today point to communication breakdowns, incompatibility, and stress or burnout as causes. Legal and societal factors also play a role: fewer people are marrying (shrinking the pool of new marriages), and those who do have higher expectations for personal fulfillment. In short, growing emancipation and awareness (plus economic pressures) have made ending unhappy marriages more feasible and acceptable.

How does Poland’s divorce rate compare with other EU countries?

Poland’s rate is still below the EU average. Eurostat data show the EU crude divorce rate is about 2.0 per 1000 as of 2023. In contrast, Poland’s rate is roughly 1.5–1.6‰. Countries like Latvia (2.8‰) and Lithuania (2.5‰) have much higher rates. So while Poland’s divorce rate has risen, it remains lower than in Western Europe. It aligns more with Central/Eastern Europe levels, reflecting cultural and legal differences.

Which regions or cities in Poland have the highest divorce rates?

Divorces are far more common in cities. Approximately 72% of Polish divorces occur in urban areas, with only 28% in rural parts. Major cities see the most cases: for instance, the Warsaw courts handled about 7,700 divorce filings in 2023, and Poznań about 5,400. By population, the West Pomeranian voivodeship had the highest divorce rate (~20 per 10,000 people) and Podkarpackie the lowest (~11.6). In summary, big cities and certain western provinces tend to have the highest divorce levels, while more traditional eastern regions see fewer divorces.

What are the most common reasons for divorce in Poland?

Polish couples most often cite communication problems, growing apart, and life stress as reasons. Modern lawyers report that disputes over everyday issues and emotional disconnect are common grounds for splitting. Unlike decades ago when spouses might have blamed “character differences,” today few divorces explicitly assign blame. In fact, about 83% of divorces in 2023 were no-fault (the court did not hold one spouse legally responsible). This means most couples agree to end the marriage together. When fault is cited, it’s usually infidelity or similar issues, but this is relatively rare (only 13% of cases cited husband or wife at fault).

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected divorce trends in Poland?

The pandemic caused a temporary drop in the divorce count. Lockdowns and court closures in 2020 led to only about 51,200 divorces, down from around 61,000 the previous year. However, once restrictions lifted, divorce filings surged again. Psychologists note that pandemic pressures often intensified marital conflicts – couples stuck at home together under stress were more likely to decide to separate. In other words, COVID-19 briefly delayed some divorces, but it also highlighted relationship problems and may have contributed to the rebound in breakups afterward.

What impact does the rising divorce rate have on families and children?

A higher divorce rate means more children and parents must adapt to life after separation. As mentioned, about 57% of divorces involve at least one child. For those children, this can mean moving between parents’ homes or living with a single parent, which can be challenging. Research suggests that some kids may struggle emotionally or academically right after a divorce, although many recover well over time if supported. For parents, divorce often brings emotional stress and financial strain (two households are more expensive than one). Economically, a family’s combined income is typically split between two homes. On the positive side, ending a conflicted marriage can eventually improve well-being for both adults, which can indirectly benefit the children. Overall, the social services system may see higher demand (for things like counseling and child support), and communities adapt by offering more family-support programs.

Are divorces in Poland usually fault-based or no-fault?

Most Polish divorces are settled as no-fault divorces. In fact, data show that in 2023 about 83% of divorce cases had no spouse legally blamed. Only around 11% of cases involved the husband being found at fault and 2% for the wife. This means most couples end their marriage by mutual agreement or through no-contest procedures. Polish law allows divorces on grounds of “irretrievable breakdown,” so explicit blame is not required if both parties consent. The high no-fault rate reflects the fact that many divorcing couples simply agree it’s best to part ways.

How difficult is it to get a divorce in Poland?

Getting divorced in Poland usually requires a court process and can take several months (or even longer if contested). Unlike some countries with no-fault or quick marriages, Polish law is stricter: couples seeking a mutual divorce must agree on property division and child custody arrangements. If spouses do not agree, or if one denies grounds for divorce, the process can be lengthier and more adversarial. In practice, this means the divorce rate doesn’t skyrocket overnight – any increase in petitions takes time to appear in the official statistics. In short, divorce is not “quick” or automatic in Poland; it’s a deliberative legal process, which tends to moderate how fast divorce numbers grow.

Key Takeaways

- Poland’s divorce rate has risen notably: about 1.5–1.6 per 1000 (2023), up from very low levels in the past.

- Social changes are driving the trend: increased gender equality, changing attitudes toward marriage, and modern stresses all contribute.

- Urban areas see the most divorces: cities like Warsaw and Poznań lead in filings; rural regions divorce much less.

- Child impact: Over half of divorcing couples have children, so the trend affects many families and social services.

- Poland vs EU: Despite the rise, Poland’s rate (~1.6‰) is below the EU average (~2.0‰), showing cultural and legal factors still keep it relatively lower.