For decades, the United States had a dirty secret. While we championed human rights abroad, right here at home—from the suburbs of New Jersey to the rural communities of Idaho—thousands of individuals (mostly minors) were forced into marriages under the guise of “tradition” or “religious freedom.”

Until recently, the US legal system was a patchwork of loopholes. In some states, a 14-year-old could legally marry with parental consent, creating a legal cover for forced child marriage.

Enter the Forced Marriage Prevention Act 2025.

This landmark federal legislation marks a seismic shift in American family law. It overrides weak state laws, closes the “Parental Consent” loophole, and finally categorizes forced marriage as a distinct form of Federal Human Trafficking.

But how does this affect you in the real world? Does it protect immigrants on K-1 visas? Does it stop parents from taking their children across state lines to marry?

At PairPulse, we have dissected the 500-page legislation. In this comprehensive US-focused analysis, we break down your new rights, the crackdown on “Interstate Coercion,” and the safety nets available for victims.

1. The Paradigm Shift: Old State Laws vs. New Federal Law

Before 2025, marriage laws were left entirely to the states. This created a “race to the bottom” where abusers would travel to states with loose laws to marry off underage girls. The 2025 Federal Act unifies this.

Here is the breakdown of the drastic changes:

| Feature | Old System (Pre-2025 State Patchwork) | The US Forced Marriage Act 2025 |

| Minimum Age | Varied. Some states allowed marriage at 14-16 with parental consent. | Federal Floor of 18. No exceptions for parental consent or pregnancy. |

| Jurisdiction | State-bound. Police in NY couldn’t stop a marriage happening in FL. | Federal Jurisdiction. Crossing state lines to force a marriage is now a Federal Crime. |

| Definition of Force | Required proof of physical violence (assault). | Includes Psychological Coercion & Fraud (Immigration threats). |

| Immigration | Spouses on visas often feared deportation if they left. | Strengthened VAWA Self-Petitioning (Victims can keep Green Card without the abuser). |

| Penalty | Often treated as a “Family Court” misdemeanor. | Felony. Up to 10-20 years in federal prison for perpetrators. |

The Insight:

This Act effectively kills the “Parental Consent Loophole.” Parents can no longer sign away their child’s freedom. If a parent tries to marry off a 17-year-old, even with a religious ceremony, they are now committing a federal felony.

2. The “Interstate Kidnapping” Clause

A common tactic in the US is the “State Hop.” If a girl in New York (which has strict laws) refuses to marry, the family drives her to a state with lax laws to conduct the wedding.

The 2025 Update:

The Act categorizes this movement as Interstate Kidnapping for the purpose of forced marriage.

- The Offense: Transporting a person across state lines (or US borders) to coerce them into marriage.

- The Power: The FBI can now get involved immediately. Local police no longer have to say, “It happened in another state, we can’t help.”

3. Immigration Abuse: The “Green Card” Trap

In the US, forced marriage often intersects with immigration status. Abusers use the threat of deportation to silence victims.

“If you leave me, I will call ICE and send you back.”

The “Violence Against Women Act” (VAWA) Expansion:

The 2025 Act bolsters the existing VAWA protections specifically for forced marriage victims:

- Confidentiality: Victims can apply for a Green Card (Self-Petition) without the abusive spouse ever knowing.

- The “Good Faith” Waiver: If you entered a marriage in good faith but it became forced/abusive, you can remove the conditions on your permanent residency without your spouse’s signature.

- U-Visas: Victims who assist law enforcement in prosecuting their forced marriage perpetrators are eligible for U-Visas (protection for crime victims).

Gut Check: Are you staying in a marriage only because you fear deportation or financial ruin? That is not marriage; that is hostage-taking. Use our Couple Compatibility Score to assess if the relationship has any redeeming emotional value or if it is purely coercive.

4. Arranged vs. Forced: The American Cultural Context

In the melting pot of the US, “Arranged Marriage” is common in many communities (South Asian, Orthodox Jewish, Hmong, etc.). The law respects culture but draws a hard line at coercion.

The Distinction Checklist:

| Arranged Marriage (Legal) | Forced Marriage (Illegal) |

| Choice: You can say “No” and the family accepts it. | Threats: “No” leads to violence, disowning, or threats of deportation. |

| Timeline: You decide when the wedding happens. | Urgency: The wedding is rushed to prevent you from going to college or dating. |

| Documents: You hold your own passport/Green Card. | Control: Parents/Spouse hold your passport “for safekeeping.” |

5. Digital Coercion & Cyber-Stalking

In the US, where smartphone usage is ubiquitous, control is often digital. The 2025 Act recognizes “Tech-Facilitated Coercion.”

- Tracking Apps (Life360/Find My iPhone): Using these apps to ensure a victim goes only to school and back to prevent them from seeking help is now considered evidence of coercive control.

- Revenge Porn: Threatening to leak private photos to the victim’s conservative community to “shame” them into marriage is a specific federal offense.

6. Implementation Gaps: The “Religious Ceremony” Loophole

While the 2025 Act is strong, it has one major weakness in the US: Unregistered Religious Marriages.

Many forced marriages in the US happen only religiously (Nikah, etc.) and are never registered with the City Hall.

- The Problem: Since there is no marriage license, the state doesn’t know the marriage exists.

- The Law’s Response: The 2025 Act states that force is the crime, not the paperwork. Forcing someone into a “Spiritual Union” is prosecuted the same as a legal marriage. However, proving these ceremonies happened is harder for prosecutors.

7. Practical Survival Guide: The US Safety Checklist

If you are in the US and fear a forced marriage (either here or being taken abroad), follow this checklist.

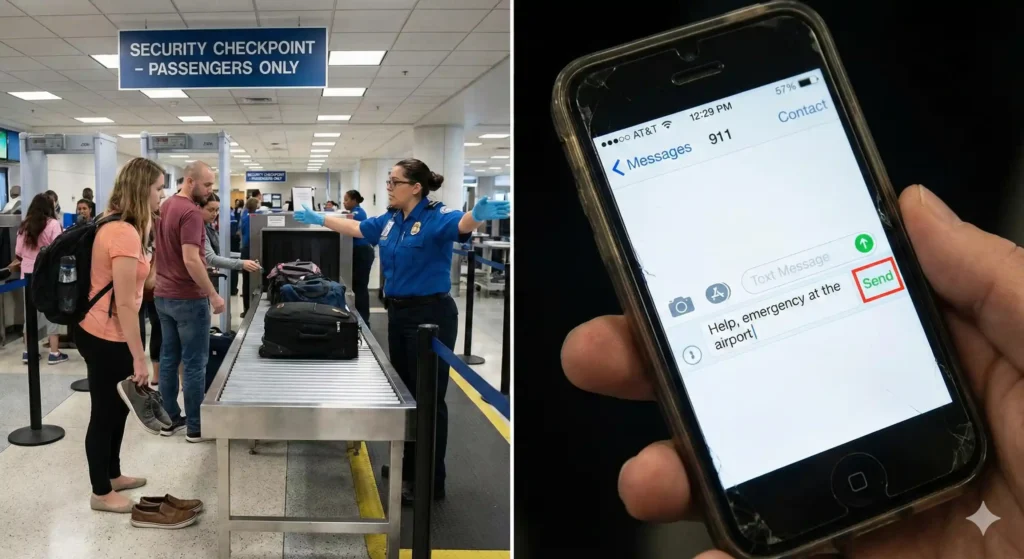

The “TSA” Safety Protocol:

- [ ] The Spoon Trick: This is crucial for US airports. Hide a metal spoon in your underwear. TSA scanners will detect it. You will be taken to a private room. Tell the TSA officer: “I am being forced to travel against my will. Please call the FBI.”

- [ ] Secure Your Status: Take photos of your Green Card, Passport, and Visa. Email them to a secure ProtonMail or Gmail account that your family doesn’t know about.

- [ ] The “911” Rule: In the US, you can text 911 in many counties if you cannot speak safely. Text: “Forced marriage, can’t talk, address is…”

- [ ] Contact Specialized Orgs: Save the number for Unchained At Last (US-based advocacy) or Tahirih Justice Center under a fake name (like “Pizza Hut”) in your phone.

8. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

I am a US Citizen, but my parents want to take me to their home country to marry. Can the US government help?

Yes, but prevention is better than cure. Once you leave US soil, it becomes much harder. The US State Department can try to assist, but they cannot override foreign laws. The 2025 Act allows the FBI to stop you at the airport before you leave if they have a tip.

Will my parents go to jail?

Under the 2025 Act, yes. It is a felony. However, many victims don’t want their parents jailed; they just want the marriage to stop. You can seek a Civil Protection Order first, which legally forbids the marriage without criminal charges immediately.

Does this law apply to minors (under 18)?

Yes, strictly. The Act sets the federal floor at 18. Even if you are 17 and want to get married, the 2025 Act makes it extremely difficult, if not impossible, in most jurisdictions to prevent coercion disguised as “teen romance.

I am on a K-1 Visa and my fiancé is abusive. If I don’t marry him, will I be deported?

No. You have rights under VAWA. You can apply for a T-Visa (Trafficking) or U-Visa (Victim of Crime). Do not let him use the visa as a weapon.

Conclusion: Freedom is Your Birthright

The Forced Marriage Prevention Act 2025 is the United States finally saying: Culture is not an excuse for abuse.

Whether you are in a high-rise in Manhattan or a small town in the Midwest, you own your life. No parent, partner, or religious leader has the right to trade your future for their honor.

If you are reading this in the dark, wondering if you have a way out—you do. The law is finally on your side.